'I thought my number was up'

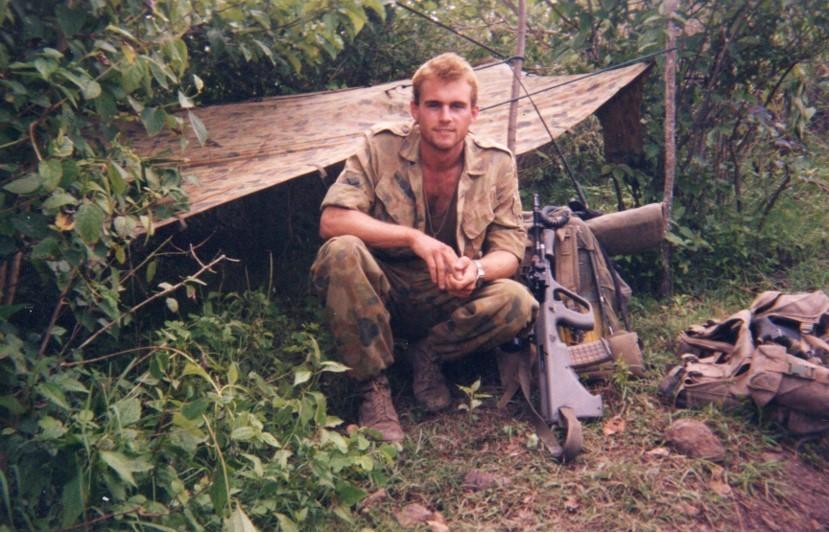

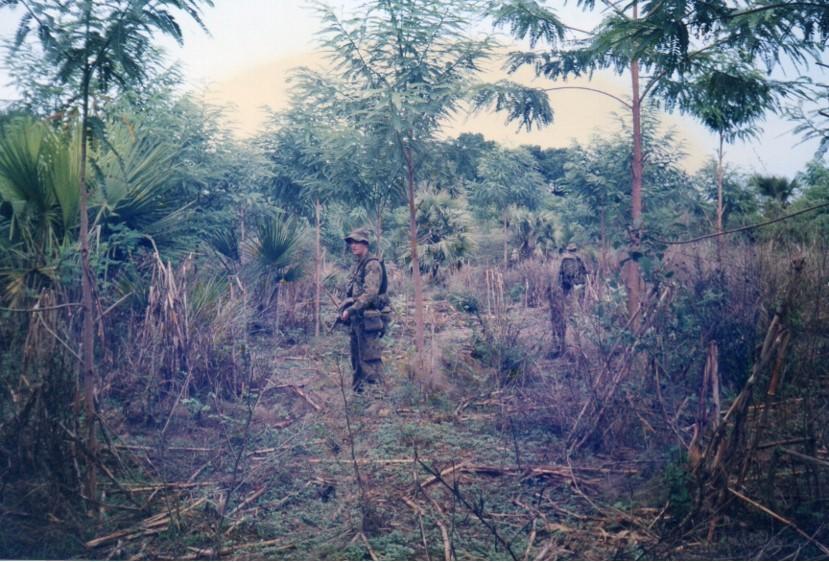

Rod Henderson out on the border at Nefolete in East Timor. Photos: Courtesy Rod Henderson

Rod Henderson thought he was going to die in East Timor when the man he was searching pulled out a hand grenade.

“We were supposed to be on rest at the Hotel Turismo in Dili, doing security for the journalists there,” he said.

“It involved being on the front gate and manning a vehicle checkpoint out the front.

“These guys came by on a moped and they looked a bit suspect.

“And then they came past a second time.

“I said to the guy I was on the front gate with, ‘If they come by again, we’re going to pull them over,’ because they looked really dodgy.

“Then they came back a third time, so we pulled them over and got them off the bike, carefully and slowly.

Rod searching a man in the courtyard of the Hotel Turismo in Dili. Photo: John Hunter Farrell

“Old mate kept putting his hands in his bag before I could get to search him and I’m like, ‘Take your hands out of your bag.’

“It was hard for us to understand each other as well, so I said, ‘Hands up, hands up,’ and as he’s doing that, he pulls out a hand grenade.

“I’m like, ‘Shit.’

“I’m this 20-something-year-old kid and I thought my number was up then.

“I brought my weapon up to his face with the safety off and this seemed to get past the language barrier because he became very compliant.

“I’m looking at this grenade, thinking, ‘I can’t shoot him anyway because there are people behind him [who could get hurt],’ and then he drops it.

“Luckily, the grenade still had the pin in it, but I’m thinking, ‘What do I do now?’

“So we searched them and took them inside and cleared them of any other weapons and then passed them on to the military police.

”But that’s military life for you, 99 per cent boredom, and one per cent adrenalin.”

In Darwin, preparing to board HMAS Jervis Bay to leave for East Timor.

It was September 1999, and Rod was serving with the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, as part of Interfet, the Australian-led International Force East Timor.

He had joined the Australian Army four years earlier.

“I joined the Regular Army when I was 18, pretty much straight out of school,” he said.

“All I wanted to do was join up, and to be like those who had gone before me, and to join the infantry and go and fight.

“Young, naïve, and stupid, right?

“You think you can save the world, but really, I was an immature kid, just out of home.”

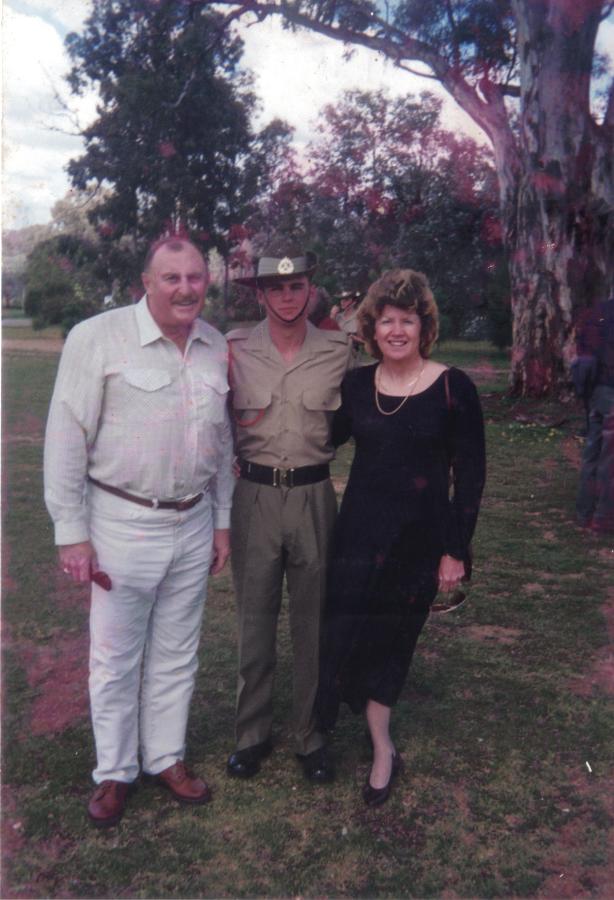

Rod with his parents, Phil and Val Henderson, at Kapooka in 1995.

His grandfathers had both served during the Second World War: one as a padre with the Australians in New Guinea, the other as a paratrooper after being conscripted into the German army in Europe.

“He didn’t have a choice,” Rod said. “The German army rocked up one day and said, ‘You’re joining,’ and that was it. He’d just had a new baby, and off he went for four years. Then he came home on leave, and my mother was conceived at that point. Then he went away for another three years, until the war ended, and he was lucky enough to surrender to the Americans and not the Russians.

“He didn’t talk a lot about the war – he was shot four times, was missing part of his head and his leg, so he had been through a lot.

“He wouldn’t speak to me [about it] until I was a bit older and I could understand. Then when I joined the army, he started to tell me more about his service, not about the awful aspects, but about service life and mateship and the comradery and the bonds that he’d formed.”

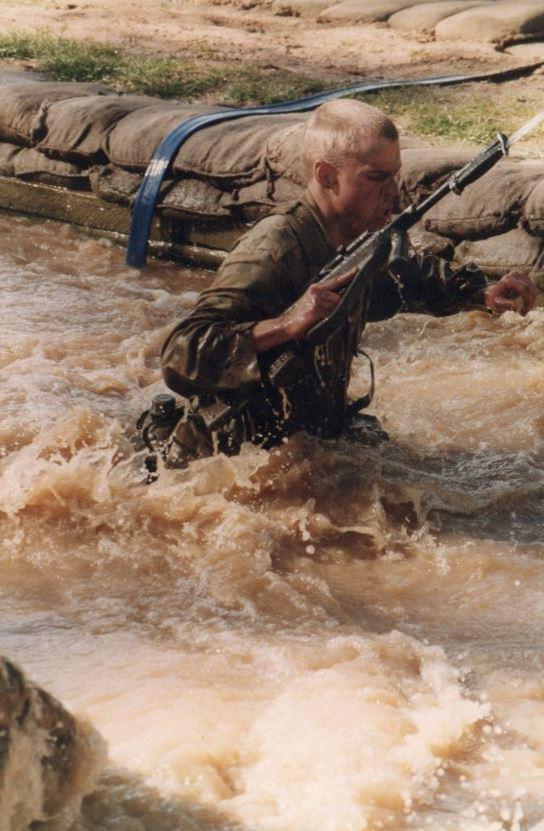

Training at Kapooka.

Inspired by his grandparents as well as his time in the Army cadets and the Army Reserves, Rod joined the Australian Regular Army in June 1995. He completed his basic training at Kapooka before attending the School of Infantry at Singleton and being posted to 3RAR, a parachute battalion based at Holsworthy in Sydney.

“I was happy I got into the School of Infantry, but I did not want to go to 3rd Battalion,” he said.

“I just did not want to go there because I did not want to jump out of planes.

“I hated heights, but the next thing you know I’m a 1,000 feet up over Nowra, staring at the taillight of a plane, going shit, shit, shit, and jumping out.

“I just didn’t like it – I don’t’ think many in the battalion actually liked it – but we did it because the guy in front of you or the guy behind you was going to do it and you didn’t want to let anyone down.

"The Infantry taught me a lot about myself and about your ability to keep going and to face awful situations and to do what you think you couldn’t.”

Members of the 3rd Battalion conducting continuation training and exercise jumps as part of the then airborne role. Photos: Courtesy Defence

Rod was in his early 20s when he deployed to East Timor for the first time.

The East Timorese had voted overwhelmingly for independence in the United Nations-sponsored referendum on 30 August 1999. Pro-Indonesian militia had then launched a campaign of destruction, arson and murder, killing approximately 1,500 people and forcing 300,000 others into West Timor as refugees. The UN then issued a resolution on 15 September, calling for a multinational force to restore peace and security and facilitate humanitarian assistance operations.

Five days later, on 20 September 1999, the first coalition force began deploying to East Timor.

For Rod, it was another world.

“We were straight into it in the centre of Dili and we were responsible for restoring law and order and security,” Rod said.

“Everything was on fire, and there was pro-Indonesian militia screaming around in their vehicles, and random gunshots going off everywhere.

On patrol on the streets of Dili.

A mounted Aslav patrol in Dili.

“We would be patrolling all day to provide a presence on the streets, both day and night.

“You’d get an hour or two sleep, then be out again for another two to three hours, then come back, maybe do security piquet, then be back out on patrol.

“It was exhausting, and scary too, because you were always told, intelligence wise, that someone was going to attack you, that something was going to happen, so as soon as some gunshots went off you thought, ‘Shit, this is it, here we go.’”

His battalion, 3RAR, had arrived in Dili aboard HMAS Jervis Bay and HMAS Tobruk. It was responsible for securing the city centre before moving to secure the western border areas of Maliana and Bobonaro and then later the enclave of Oecussi.

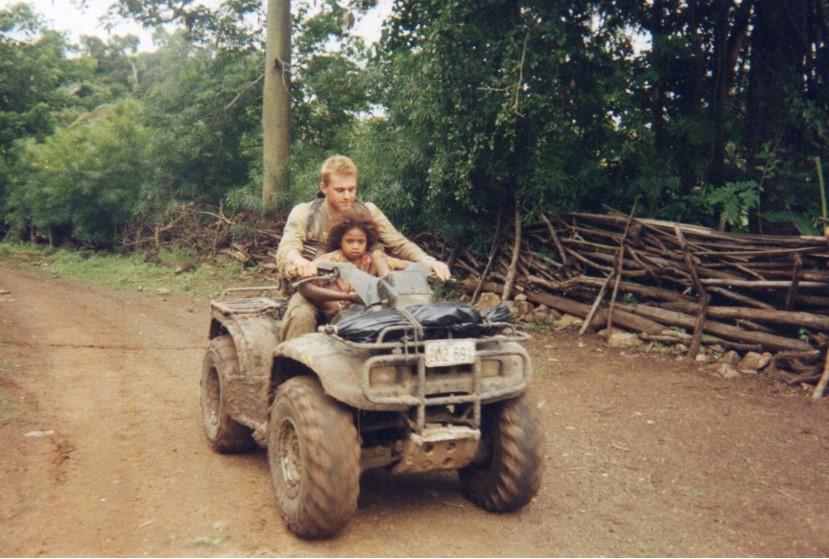

Taking the locals for a ride in Nefolete.

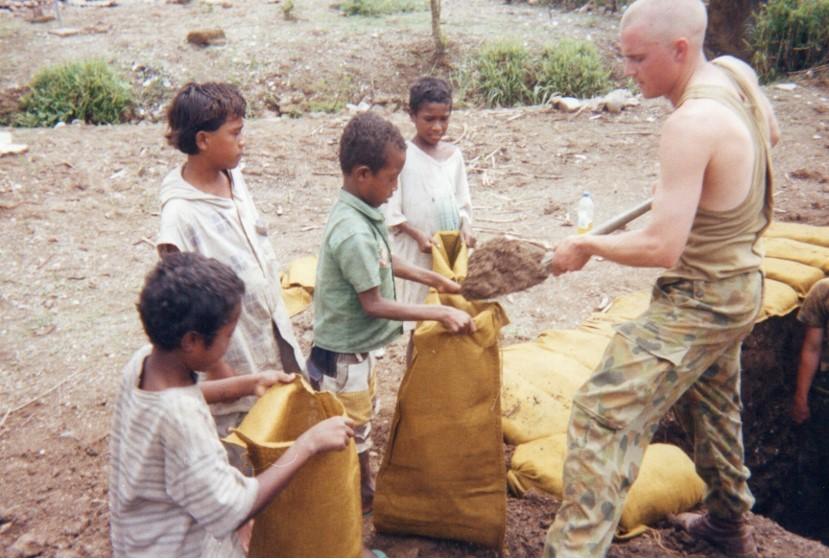

Filling sandbags with the locals whilst digging pits at Bobonaro.

“It was very confronting, especially as a young bloke,” Rod said.

“I was very inexperienced and probably very immature. I was 21, 22, and had no idea what I was getting myself in for.

“I thought I was invincible, and I was just going along with my mates.

“I thought everything would be great, and it’s not until you get on the ground you think to yourself, ‘Shit, I’m way out of my depth, I’m going to get shot.’

“You’re full of self-doubt, but you don’t want to let anyone else down.”

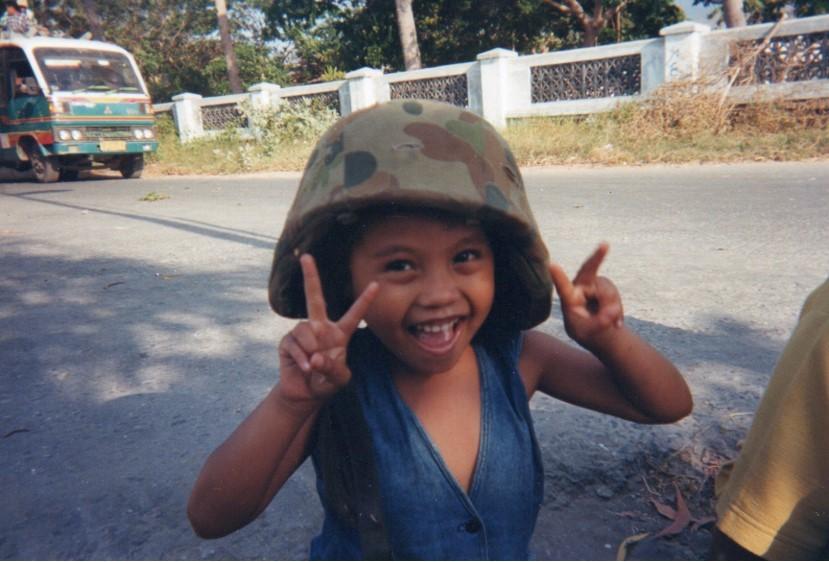

Meeting one of the locals in Dili.

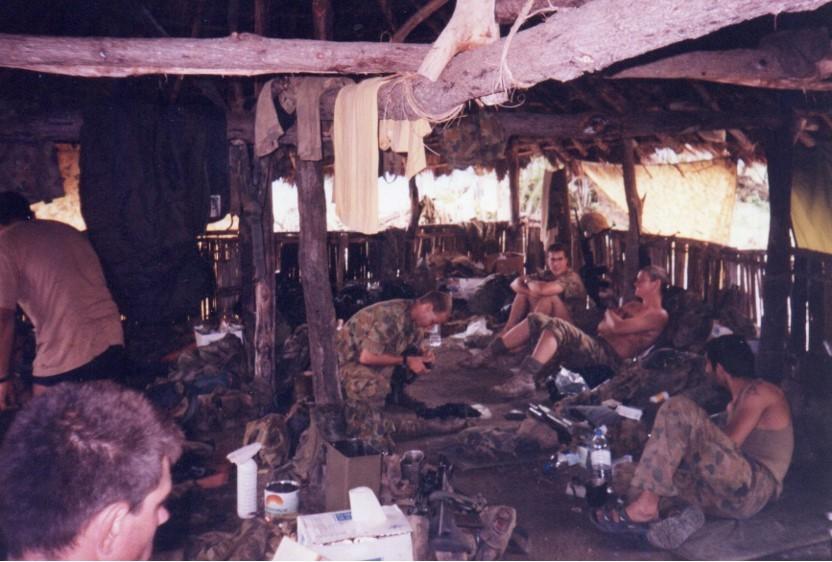

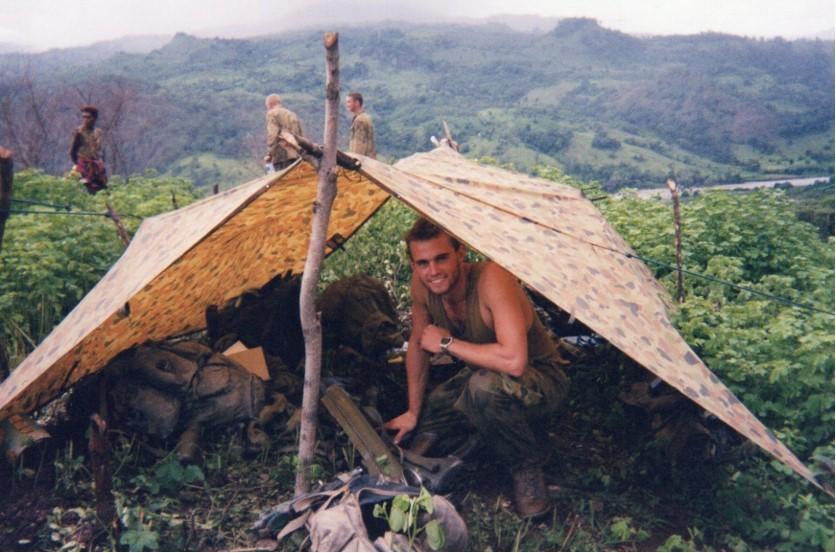

The platoon admin area in Nefolete prior to leaving Oecusse.

The battalion was primarily engaged in searching buildings, finding and disarming militia, and gathering intelligence from locals.

During one building search, Rod’s platoon located and seized the headquarters of one of the more notorious militia groups.

“We formed a checkpoint outside after searching the militia headquarters,” Rod said.

“They’d only just left and all the people out the front started to go crazy, yelling, ‘There’s militia coming, there’s militia coming,’ so I got sent out the front with half of my section, and lo and behold, the very vehicle that everyone was saying was coming, started coming up the street.

“The platoon sergeant said, ‘Hendo, stop that car.’

“And I’m like, ‘Just my luck.’ So I walked out onto the road with my rifle and told them to stop.

Australian soldiers detain suspected members of the militia at their compound in 1999. Rod is pictured front right. Photo: Courtesy Jason South

Rod with his section commander Andrew Baker.

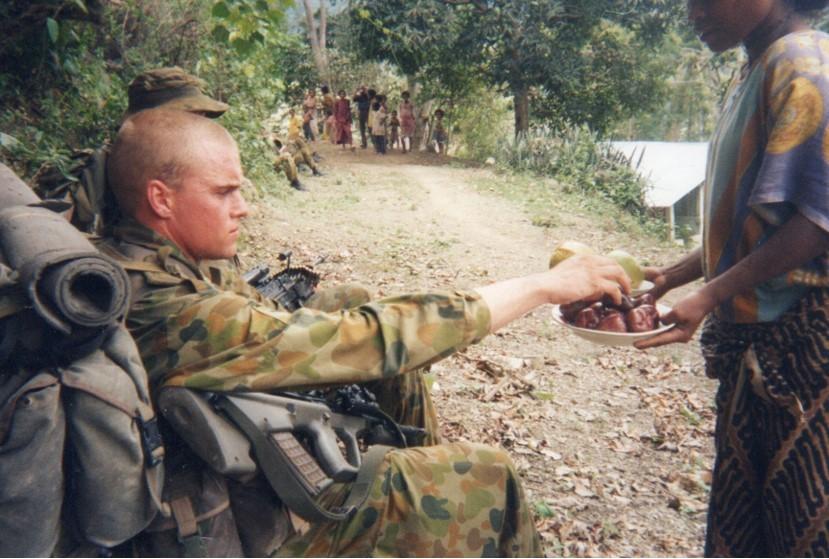

On patrol in Bobonaro, stopping for a break with the locals.

“They pulled up right beside me and there’s five really dodgy-looking guys.

“Everyone’s got eyes like dinner plates at that point, just waiting for someone to move quickly.

“It would have been just chaos, so we got them all out, one at a time, and started searching them, and got everything secure.

“Within minutes, an Indonesian Army tip truck pulled up at our checkpoint. It was full of militia-looking blokes who started screaming at us about something or other. No one understood why, but they started pointing weapons at us, so we pointed ours back, which began this weird stand-off that came out of nowhere.

“Fortunately our platoon sergeant could speak Bahasa. He came outside and started yelling at us like we were being scolded by our father for being silly, and he must have given the militia the same serving in Bahasa.

“It worked because everyone put their guns down and they drove off, but I remember thinking later that day, ‘Did that really happen?’

A view of the football stadium in the early days of Interfet.

“On the five people we detained, we found lots of money, some human teeth and hair, and lots of names and identifications – just really bizarre stuff – so we arrested them and had to take them back with us.

“We were staying at the Dili football stadium at the time and the vehicles couldn’t come and pick them up so we had to walk them about a kilometre or two back to the stadium.

“The locals were either side of the road, throwing rocks and running out, trying to hit them, and so we’re now trying to protect the militia guys from the locals.

“It was a really long, at times terrifying and bizarre, day.”

In East Timor, the battalion was also responsible for helping to locate and distribute supplies. While carrying out these tasks, soldiers found evidence of atrocities. One of the more gruesome aspects was the discovery of bodies, sometimes as part of isolated incidents, but also mass graves from massacres.

On patrol at Oecusse.

With the AFP marking out a mass grave at Passabe.

For the boy from Newcastle, it was a confronting experience.

“One hundred per cent,” Rod said.

“Just the smells, everything. It’s very confronting, but you had a job to do, and that was what you were trying to focus on.

“When you look at other peoples’ stories and what they had to go through, it helps you put things in perspective.

“You might think the most awful thing has happened to you, but actually, a lot of people have been through a lot worse.

“We went out and helped the Australian Federal Police mark out and identify a mass gravesite at Passabe.

“That was eye-opening as a young fellow too; just how callous people can be, and how they were killed, and how they were treated.”

On an observation post at Nefolete.

Taking a break on a patrol.

Rod would spend almost 18 months serving as a peacekeeper in East Timor on various rotations.

He returned with a detachment of Black Hawk helicopters from the 5th Aviation Regiment in 2003, 2004 and again in 2006. He had made the decision to retrain as a loadmaster and door gunner while serving in East Timor in 1999.

“I remember we were right out at the border at Oecussi and we were just sitting in mud,” he said.

“We were at an observation post overlooking the border where our section had made contact with a small group of militia.

“Our first scout shot a man who was raising his rifle to shoot at him.

“My half of the section was up above on overwatch, and we could see the other militia members raising their weapons.

Waiting to leave Nefolete in 2000.

“We fired in support of our half section and the man I engaged dropped immediately. I remember oddly not feeling any emotion about it, but clearly I wasn’t as good a shot as I thought I was, because the cheeky bloke popped up again and started legging it back up to his mates on the hill.

“Things then started to settle down, and it was at that point that the reality of what had just occurred hit me, and it’s something I still remember to this day.

“After that bit of excitement, we were just sitting in mud for weeks and weeks at that observation point.

“You’re whole day consisted of getting up, pulling a two-hour piquet on overwatch, and then for the rest of the day you’d try to read a book, take the piss out of each other, or pick mud off your hands, and your face and your feet, and then you’d go and sit in the mud on piquet all over again.

“I just thought, ‘You know what, there’s got to be more than this. There’s got to be more to the Army than picking mud off your face, right?’

“And I remember seeing a Black Hawk flying over and coming in and doing a resupply and I’m like, that’s it.

“I’ve got to go and do that.”

Rod Henderson went on to serve as a helicopter loadmaster and door gunner with the Chinooks in Afghanistan. Read about his experiences here.